The name Chocolate Factory certainly evokes a reaction where lots of other games may not. On mentioning it to friends I got at least one ‘ooh chocolate’ (or something along those lines) in response, and whilst, when you look at the game, you think it could have a lot of different themes assigned to it, it’s one that works nicely, is appealing to a lot of people, and is fairly unique. Once you get into the game, you’ll find that it is a fairly involved engine-building game (a mechanism for which I have expressed my fondness on numerous occasions), but also quite elegant in its simplicity.

Chocolate Factory is played over six days, Monday to Saturday, with each day of the week being a new round. Depending on the day, each player gets a certain amount of coal (starting with five and increasing by one each day) to run the machinery in their factory, which all takes place on your player board.

Chocolate Factory The Draft

Before any of that though, a draft will occur to see which new factory part you’ll add to your factory, and which employee you will have this round. Depending on player count, a certain number of factory parts will be available, and you will perform a snake draft to choose one of each card type. A snake draft is where the player with the first player marker will choose first, but also last, so as an example, in a three-player game, the first player picks, then the second, then the third, and then it goes back in reverse.

The factory parts will do various things for you, from upgrading chocolate to duplicating it, and this is all indicated by symbology, which, once you’ve learned what the basic symbols mean, are all straight forward. In the top left is how much coal that factory part requires to be operated, and that’s all that makes up these cards. The trick is knowing where in your factory to place them to get the most out of them, and how to use the limited amount of coal you have wisely to use the right part at the right time. When placing new parts, you can either place them into an empty space on your board, or cover up any parts already there, including the three pre-printed parts each factory has. Once covered, these parts can no longer be used, so it may be best to place in empty spaces, but you also want your best parts as close to the beginning (left) of your factory, so that you can use them more quickly, meaning you may need to cover up the pre-printed parts.

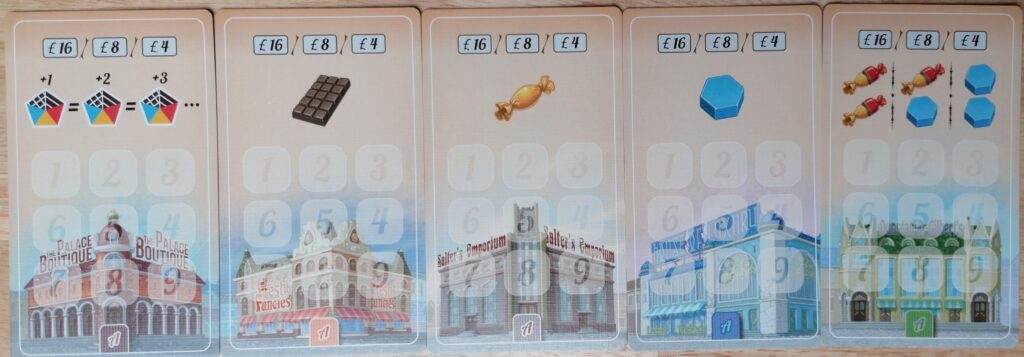

The employees also represent multiple things for you. Each one will have either an ‘Action’, ‘Benefit’ or ‘Gift’ shown, which are all explained in easy-to-follow text. A gift is just an immediate bonus, benefit will be based on a condition being fulfilled, and an action can be used at any point during a round. These will often be attractive prospects, and may well determine which one you choose, but you always need to pay attention to the ‘Department Store’ that they represent, printed along the bottom of the card. One card from each of the five department stores are drawn for the draft, and based on which one you choose, you will not be able to sell chocolate for this round to the other four. Though the decision surrounding factory parts is an important one, as it will impact how your engine runs, potentially for the rest of the game, I think this one is just as important. You may see that one or more opponents are shooting up one or more department store tracks, meaning you may want to draft that card to either stop them getting further along it, try to compete with them, or both. Or you may just want to ensure your position on a track where you’re already the leader. And because you score more points at the end of the game for selling to more different stores (not necessarily being high up on the tracks, just being on them), you may just want to split your attention between all five.

Chocolate Factory The Round

Once you’ve drafted your cards, a round of Chocolate Factory plays out fairly simply, but as you get to later rounds, your options grow, adding more and more depth to the decisions you are making. A round is made up of three ‘shifts’. A shift consists of placing a cocoa bean on one of your conveyor belt tiles and pushing it into the space furthest to the left on your player board. You’ll spend coal to convert that bean into whatever the parts you have in your factory allow (if you want to that is), then play another shift, placing another bean on the next tile and pushing it in, simultaneously moving the first bean (or whatever it has been converted to now) to enter your factory once to the right. The rulebook states that you can play this part of the game simultaneously, but for at least one or two rounds, I would suggest going one at a time, just so that each player sees how it works.

The department stores in Chocolate Factory show a specific requirement, and you will only be able to sell to them (if you have the relevant employee card) if you have the order they need. As an example, ‘Fresh Fancies’ (second from the left in the picture) require a chunky bar of chocolate. When selling to any of these stores, you can sell as many units as you can, to move further along the track. Each store track has nine spaces, and you can’t go beyond this. At the end of the game, you will check who is highest on the track, and that person will get £16 (money represents points in Chocolate Factory). The second highest will gain £8, but only if they are at least half (rounded up) as far along the track as the highest. As an example, if a player is on space nine, you will need to be on space five or higher in order to claim second place. This also means that, if second place doesn’t score, neither does third (who would normally gain £4), so you will need to watch out for that.

As mentioned above, you’ll also score based on how many department stores you have been able to sell to over the course of the game. If you’ve sold to three of them, then you’ll gain £6, if you’ve sold to four you’ll gain £12, and if you’ve sold to all five, you’ll gain £24, so even if you’ve not managed to shoot up any one track, it’s still likely you’ll score something.

The department store cards are also double-sided, with an A and a B side, with each side indicating new requirements. They don’t massively change the game, but they give you a nice bit of variety, not only in changing what’s needed, but also potentially changing which factory parts you choose, so that you can get what you need.

Chocolate Factory not only utilises end game scoring, but also in-game scoring, and does so in a nice thematic way; through ‘Corner Shops’. At the beginning of the game, each player will take a small, medium and large corner shop card, face-up in front of them. At the end of a round, when you sell your chocolate, you can fulfil these, either instead of or as well as, department stores. Small corner shops only have one step required to complete the card, mediums have two and large have three. You can fulfil as many steps as you want to (as long as you can do so), but that’s your decision. If you’d rather save that chocolate for a different order, then you can do so (though you can only save two pieces of chocolate from round to round that aren’t still in your factory).

Whenever you complete all steps shown on the card, you can take a card to replace that one. The good thing is, you’re not limited to taking the same sized corner shop. If you complete a small one, you could, if you wanted, take a large one to replace it, and while it will take more chocolate to complete, you will get more money in the long run. I enjoy the fact that you’re not limited, as it introduces a bit of push your luck. If you’ve got plenty of rounds left, it may be fairly safe to assume that you’ll be able to do a large corner shop or two. However, like with the department stores, you score at the end of the game for how many you’ve done, though this time only the person who has completed the most gets points (£12), so you may well think that taking lots of small corner shops is the way to go.

The production of Chocolate Factory is excellent. Each piece of chocolate is a 3d representative, rather than just a cardboard token. The player boards are dual-layered, with the conveyor belt through the middle being a single layer, allowing you to slide your conveyor belt tiles in easily and effectively. Even these tiles are differently patterned for each player, giving each person a sense of individuality. The employee and department store cards are nice and big, so that they’re easily read, whereas the factory parts and corner shop cards are small enough to not be imposing, while still being big enough to be usable. I especially like the art on the factory parts, where there’s an illustration of not only the part but also on the belts is the chocolate that it is making. It’s a completely unnecessary detail, but it’s so evocative of the theme and gives you a greater sense of what you’re doing.

In terms of mechanisms, Chocolate Factory combines two of my favourites; engine-building and card-drafting, and though there are quite a few games that utilise these two together, I’m happy to have this one. Puzzling out what parts you’ve already got on the board, against which are available in the draft, taking into consideration the employees, corner shops and chocolate left in your factory from previous rounds may, on the face of it, sound like a fair bit, but for me is the right amount of depth I want from this. Add to that the brilliant production, and this one hits the mark for me. One thing I will mention is that, especially in later rounds, factory parts and corner shops may come up for you which just don’t match the rest of your engine, and you can feel like you’re perhaps punished a little for specializing earlier, if you have, but I think that even if this happens, you still have a lot of options available to you. Overall, one that I’m glad to own.

| Prices delivered by BoardGamePrices | |

|---|---|

| Chocolate Factory £40.50 with shipping, in stock! Buy now See all 21 offers! |