Architects of the West Kingdom kicked off a trilogy of games from Garphill Games (in fact their second trilogy) set in a fictional historical world of their design. The theme is there, and you’re doing things within the world that make sense, but, for the most part, it could be set almost anywhere. Then again, I like the fact that they did create a unique setting, rather than just using a bog-standard medieval England theme.

When looking into this game, as with most, if not all, of my collection, it was the mechanisms that drew me in. Worker placement is one of my favourites, but what set this apart was how it was implemented. Whereas with a lot of games using this mechanism, where you will start with some workers and have an opportunity to recruit more (or some kind of variation of this), Architects of the West Kingdom gives you all of your twenty workers at once. Now, some may start on the board depending on the character you’re playing as, so won’t be immediately available, but it’s very easy to reclaim these.

At the beginning of the game, each player is dealt a different character. If you’re quite new to board games, and/or if you just want to ease yourself in, you can play on the symmetric side, and the game will still play nicely, but I would always recommend playing on the asymmetric side. The only thing added in terms of complexity is that each player gets a special ability, though it is printed clearly on the board, and it adds a fun level of variety. Some people will start with more resources than others, for example, but then will start with fewer workers immediately available to them or start lower on the ‘virtue’ track.

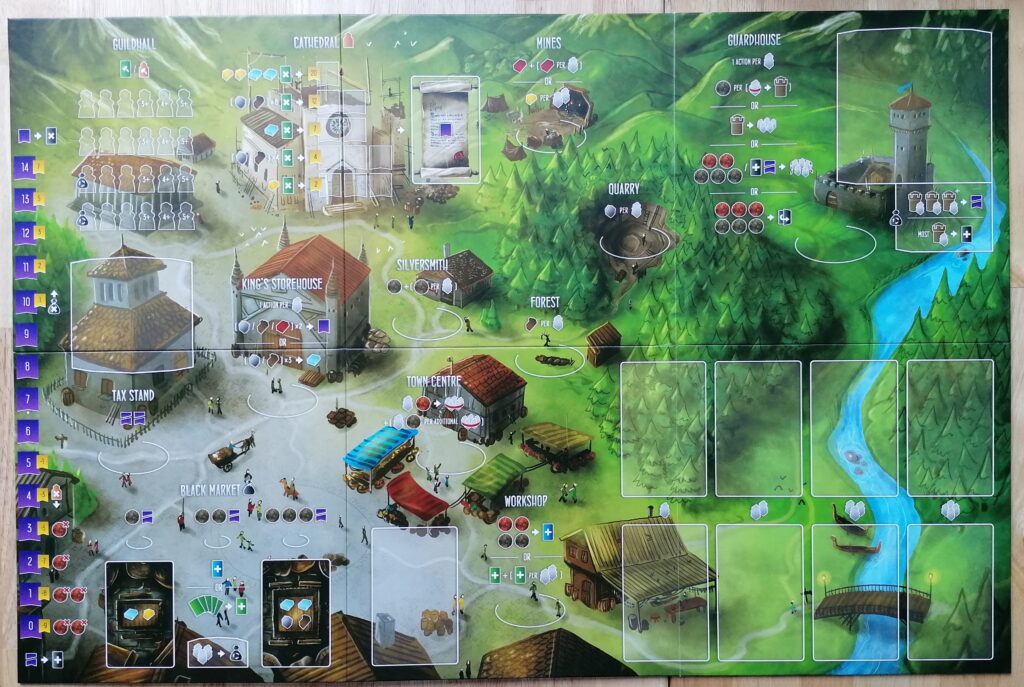

Virtue is a concept that continues throughout the trilogy, but it is at its most simple in Architects of the West Kingdom. Along the left-hand side of the main board, this track will gain or lose your points at the end of the game, but also, depending how high or low you are on it, one of the actions on the board may not be available to you. If you climb it high enough, you’ll no longer be able to take the ‘black market’ action, one space on the board where you can go to gain resources quickly and cheaply. On the flip side, if you drop down low enough, you will no longer be able to contribute to the cathedral, a very powerful part of the board where you can gain plenty of points. To offset the negative of not being able to go here, actions will also cost you less the lower you are on the track. Though I enjoy this from a thematic point of view, in my personal experience I’ve found it to be slightly unbalanced, as it seems like you’re more likely to do well if you’re towards the top end of the track.

Two other main ideas are retained throughout this trilogy of games: debt and tax. With most actions that require payment, some of the money you pay is classed as tax (indicated by a red coin), meaning it will be placed into the tax stand (another spot on the main board). A player can choose to go here on their turn, take all the money, and drop down two spaces on the virtue track, so depending on how much there is on that spot, it could be very tempting. Here is where the discounts come in for the less virtuous players, as they either pay less or no tax on actions.

The main ways to gain a debt card in Architects of the West Kingdom are to drop below zero on the virtue track and to have the most workers in prison during a ‘black market reset’. The prison aspect is, for me, the most interesting part of this game. When I said earlier that some of your workers may start on the board, this is where they start. Throughout the game, players will have opportunities to take an action to ‘arrest’ a group of workers from one or more spots on the board. If they ‘arrest’ their own workers, they just take them back into their player area, but if it’s an opponent’s workers, then they keep them in a separate area of their player board, until they take them to prison, trading them in for one coin per worker. Black market resets happen when either all three spaces at the black market have been taken, or when you get to a certain point in the game. There will be, at the very least, two of these in the game, and they can sometimes sneak up on you, so you’ll need to be aware of them. A debt card, at first, will be worth minus two points each at the end of the game. However, you can pay them off, flipping them over to make them worth plus one point instead, and though it usually costs quite a lot to do this, it could be part of your strategy.

I mentioned that Architects of the West Kingdom is different in relation to the distribution of workers, but this feeds directly into another thing that sets it apart. Where with a lot of worker placement games you will get an opportunity, perhaps at the end of a round, to take all of your workers back, you don’t here. There are no rounds in Architects of the West Kingdom, and each turn you’ll just place another worker out on any space you can afford. You can put one worker after another on the same action space, increasing the power of that action. For example you’ll gain one stone for the first worker you place in the quarry, but two for the second, and so on. Doing this, however, will make the space more attractive for someone who wants to arrest a group of workers, as it’ll gain them more coins when they take the workers to prison. It’ll also mean that more of your workers are in there, potentially losing you virtue and gaining you a debt card, so you might want to spread yourself a little thinner, performing lots of different, but less powerful actions.

This is where the genius of the arresting system comes in again for me. As I mentioned, you can ‘arrest’ your own workers, bringing them back to your area, which may be much needed, as you might be running out of workers, but if you’ve spread yourself too thin, it’ll be much more difficult to do this. So you might want to build up as many as you can on one action space, but then other players will target you, getting there before you can, profiting from your decision. However, again, you may be running low on workers, and so you really want them to put your workers in prison, so that next turn you can go and release them. The worst thing for you is if someone keeps your workers on their board, instead of taking them to prison, as the only (main) way to retrieve them is by paying your opponent. But it might be bad for them to keep your workers too, as they may really need the money, and they won’t get paid for them until they take them to prison. In my eyes, this is by far the best part of the game, and it also flows incredibly smoothly, so even if you’re confused when reading or hearing about it, in game it becomes easy to understand.

The two main decks of cards in Architects of the West Kingdom are the building deck and the apprentice deck. Buildings will give you points at the end of the game, as well as another ability, which activates either immediately or at the end of the game. Some buildings even have both, but these will usually cost the most. They will always come with a resource cost of some kind, but as you get to the more powerful buildings, there will be further requirements, indicated by the symbols in the top-left of the cards (axe, paintbrush and hammer).

This is where the apprentices come in. Each one will cost money to take, and each will give you an extra ability, allowing you to do something extra when you perform a particular action. For example, with the Conspirator pictured, each time you go to the town centre you will pay one less untaxed coin. Each apprentice also gives you one of the symbols required by the buildings, so your faced with a choice when hiring them. Do you try to get each symbol, as you can only hire five (as standard) apprentices, or do you focus on their abilities, and just go for less powerful buildings?

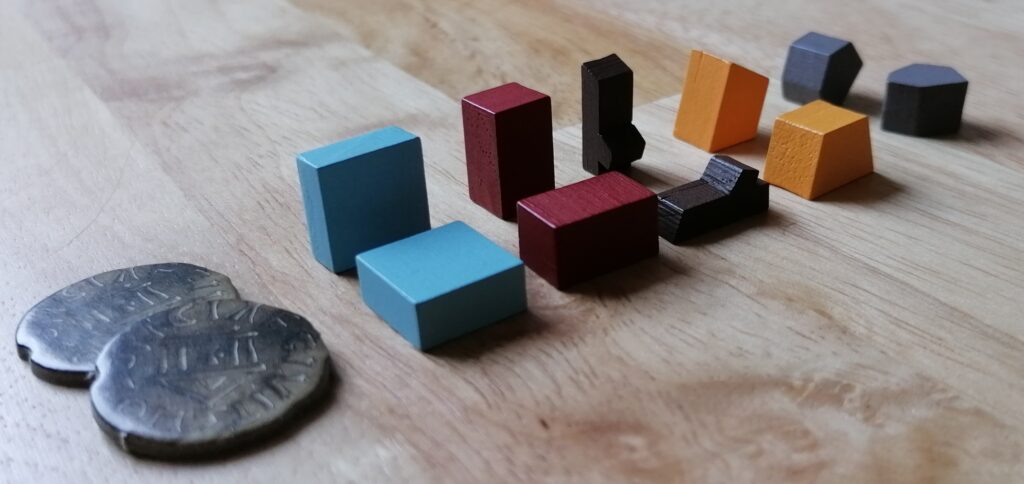

Production-wise, for me, Architects of the West Kingdom does very well. The board is very clear, and the art is good on it, helping put me in the world. Not only did they choose the colours for each other for the resources quite well (though the brown and red could be mistaken), they are different shapes, making them even easier to distinguish, rather than giving you generic cubes. The workers, though fairly small (I suppose they have to be as you have a lot of them) feel nice, with rounded edges as opposed to straight lines. Then we come to the character art. Some people dislike it in this game, as well as any other work from this artist (he does a lot, including the others in the trilogy), but I’m a fan of it. It’s distinctive, and oddly cartoony but also realistic, in a good way (for me at least).

I will discuss the other two games in the trilogy over the coming weeks, so I won’t give my verdict as to my favourite yet, but I will say that I enjoy Architects of the West Kingdom quite a bit. I think my opinion of it has fallen a little, and I think that’s down to how the virtue system is implemented. Aside from that, I enjoy the simplicity of the actions available to you, but also love the hidden depth of the game, making it a very interesting game for me.