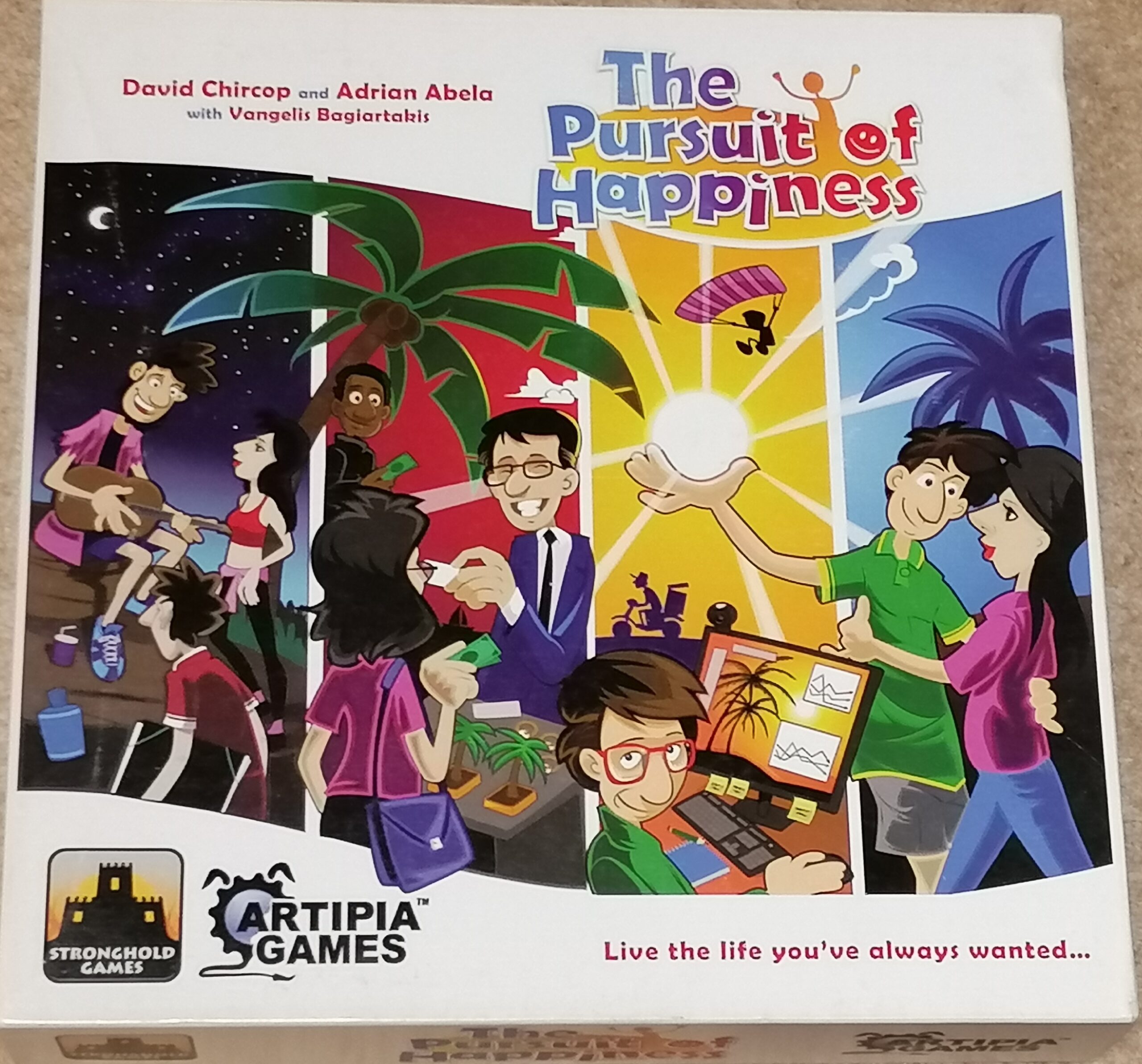

I have heard The Pursuit of Happiness described as the ‘Euro Game of Life’, and I suppose you could definitely see it that way. It is a worker placement game where you live your life, from being a teenager to death. It sounds a little morbid, but it’s not something you’re fighting against, rather it is, much like real life, something you’re trying to delay for as long as possible so that you can fit in more experiences.

This was amongst the first games I bought for my collection, and it was the theme that instantly attracted me. Often board gamers, including myself, will gravitate to something a far reach from reality, to feel like they’ve escaped into another world. The Pursuit of Happiness, though different in that it is probably the closest game that I have played to reality, still allows you to live out your life in a fantastical way. I enjoy being able to play the game with no fear of consequence other than just not amassing the most points possible, as opposed to reality. However, I completely understand that some people may still want to play the game with the same morality that they have in their own lives, as it may still feel wrong to them to make decisions they would find immoral or wrong, despite it just being a game. I have an issue with choosing to go down a bad path in video games.

The Pursuit of Happiness is played over a maximum of 8 rounds, but no minimum. This is because of the stress track towards the bottom right of the board. You’ll start the game in position number seven on this track, as indicated by the white arrows. There are plenty of things over the course of the game that will stress you out, meaning you’ll move up on the track, and if you ever would move your marker off the right-hand side of this track, then you ‘die’, and your game is over. Notice I say your game, as everyone else will continue to play until they move off the end of the stress track as well, or until the end of the 8th round. I do think that the stress track is an intelligent and thematic integration into the game, but I do have a problem.

It is split into seven different coloured sections, and as you amass stress you will continue to move to the right, no matter which coloured section you are moving into. There are always ways to destress in the game, but you can’t move your marker into a different section to your left unless you obtain a card with the ‘good health’ (heart) symbol. These cards are quite rare, and when they eventually do come up, everyone will be scrambling for them, even if the other effects are not very helpful to them, because this ability is so valuable. This is because, as you get into later rounds of the game you will automatically take stress, to indicate that you’re getting older, and if you’ve not been able to obtain a good health symbol, then your game is more than likely going to end before someone who has. This is probably the only part of the game where I feel that the theme gets in the way.

The other track in The Pursuit of Happiness is the ‘short-term happiness’ (STH) track, and whilst only a small part of the game, I do think that this is a nice addition. There are quite a few opportunities to obtain STH in a round, and it will determine who is the first player for the next round, but also you will get discounts on cards equivalent to your STH (or, if you’re into the negative, you will have to pay more). It does reset at the end of every round however (because it’s only short-term), so you don’t have to worry too much if you’ve dropped down the track.

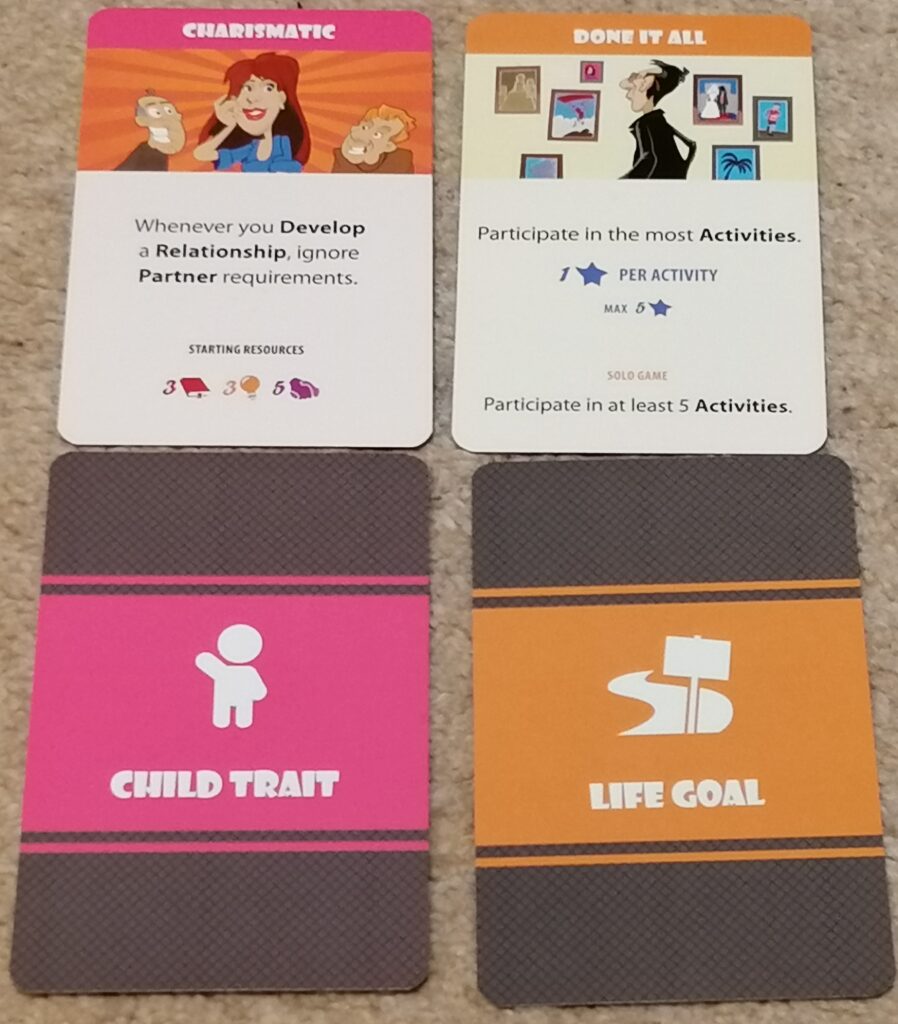

As with life, each player is a little unique in The Pursuit of Happiness. At the beginning of the game each player will be given two ‘child trait’ cards, and choose one of them to keep. These will indicate which resources you start with, but will also give you an asymmetric power for use throughout the game, and each seem balanced in terms of how powerful they are. I enjoy that you’re able to choose from two, as you can immediately decide on one direction you want to go in. I also like the fact that they don’t force you down a path. Though they are helpful benefits, they tend to only apply to one action, and because one way to accrue stress is by repeating the same action twice in a round, you’ll probably want to branch out.

Something that adds a nice bit of interaction in the game is the ‘life goals’. These are common goals for each player to aim towards, but only one player can achieve. Most things to which they relate, for example participating in the most activities (as in the life goal pictured), are openly known to every player, so it is easy to tell if you’re going to win something or not. This could be an issue for some people, as not knowing may add to the anticipation at the end of the game, but based on what type of game this is, I don’t really have any issues with its absence here. Also, because they aren’t worth very many points, it’s not going to be something that will ruin your game if you can instantly see that someone has beaten you for the goal.

At its heart, The Pursuit of Happiness is a very simple worker placement game. Place one worker out onto an action and gain the benefit. The benefits themselves are also fairly basic. The actions on the board allow you to gain more resources, gain a card, move up on the stress track to gain more actions, or ‘rest’ to destress. Where the depth of the game comes in is how the rounds work, and through the various cards. In the first round, as a teenager, the ‘get job’, ‘develop relationship’ and ‘overtime’ action spaces are unavailable, and in old age (rounds six, seven and eight) the overtime action becomes unavailable again. Thematically, it’s to indicate that at these points in your lives, these aren’t actions that you’re going to be taking (though some people may well argue), but it works quite nicely, allowing you to plan around this by prioritising certain things at certain times.

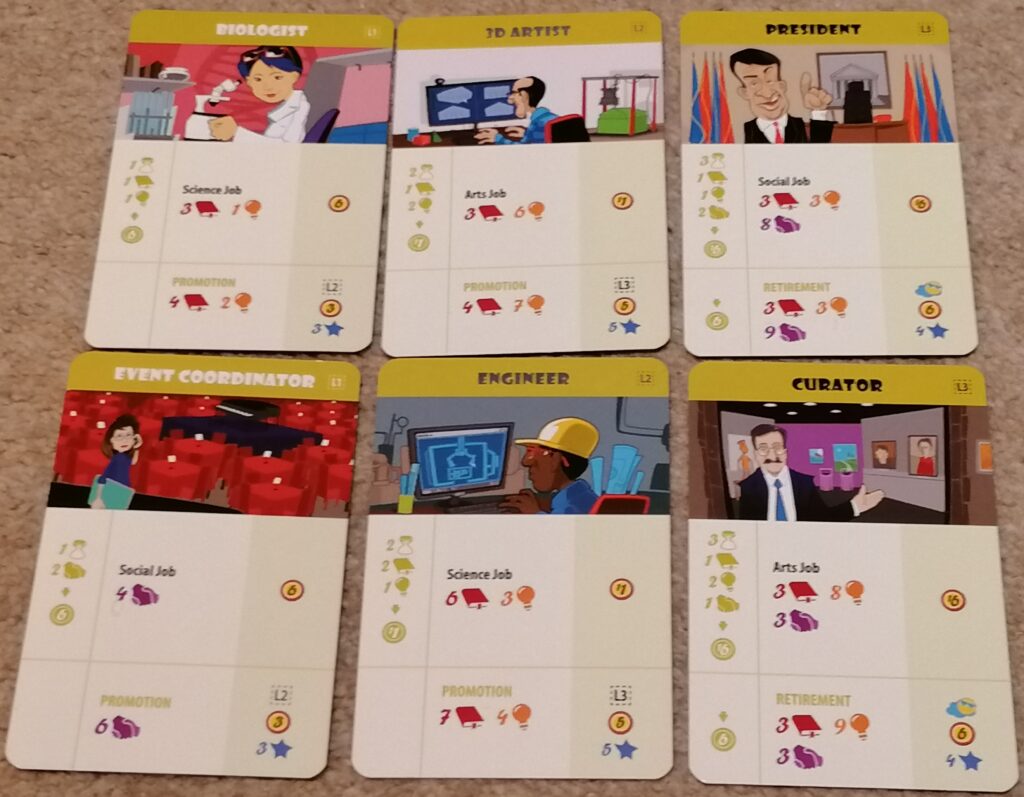

As you move through the game, more and more of your actions will be spent on cards you have in front of you, as opposed to on the board. You can place a worker on most project cards to advance a level, paying the required resources to advance, gaining the benefits on the right. The slight exception is group projects (the middle card in the picture), where multiple people can contribute, taking up to two roles each. The other type of card on which you can place a worker are jobs. There are three levels of jobs, and in the lower part of level one and two jobs is a ‘promotion’ action. In order to take this action, the next level up in that type of job has to be available on the board. As an example, if you have a level one Science job, you can only be promoted if a level two Science job is available on the board. Instead of a promotion action, level three jobs have a ‘retirement’ action, which costs quite a lot of resources, but will free up a lot more options in the game.

Perhaps my favourite part of the game, as I feel that it’s incredibly thematic, and adds a wonderful amount of complexity to the game, is the ‘upkeep’ system on the cards. On the left hand-side of a lot of cards will be some additional symbols, which will indicate what you have to pay at the beginning of each round to keep these cards, and the amount you will have to pay will increase as you advance on the levels. With jobs, you’ll usually end up having to commit at least one of your workers, as well as some resources (indicating what traits, for example creativity, you will need to keep your job). With partners, dating someone doesn’t usually have an upkeep, but if you advance to being in a relationship, there will be some upkeep, and raising a family will require even more. Again, this will predominantly be one or more workers, and having to give these up, indicating the amount of time you’re committing to these various things, really pulls me into the theme. Upkeep also comes with ongoing benefits. Your job will pay you a salary, and you’re partner (depending on who they are and what level your relationship is at) will give you various benefits, from long-term happiness (points), to STH and extra resources, such as intelligence. This is where the puzzle really shines for me. Do I want this higher-level job? It will gain me more money each round, but the upkeep is much higher, and it takes away three of my actions.

Overall I think the production of this game is good. The art is sort of cartoony, while also keeping a sense of realism. The board is clean and player-friendly in terms of its layout. The resources, rather than just cubes of different colours, are tokens, which clearly indicate what they are and how much of that resource they represent. Your workers are shaped like hourglasses, adding yet again to the theme of the game, as they represent time. I do sort of wish that the markers for tracks and the levels on your cards were more than just small cubes, but they’re still functional.

One thing I am impressed by is the partner cards. They are double-sided, with one side representing a male partner and one side representing a female partner. The upkeep, benefits and costs are the same on both sides, but it’s the inclusivity of it that makes me happy. It’s an easy thing for a publisher to include in a game, and though it doesn’t include everyone, it’s a step in the right direction.

The Pursuit of Happiness is, for me, a friendly game. One that I can always choose and just have fun with. It lets me play how I want to play, giving me plenty of options throughout the game. As I have mentioned, I do have some issues with it, and it can be a little frustrating, but I suppose, as they say, that’s life