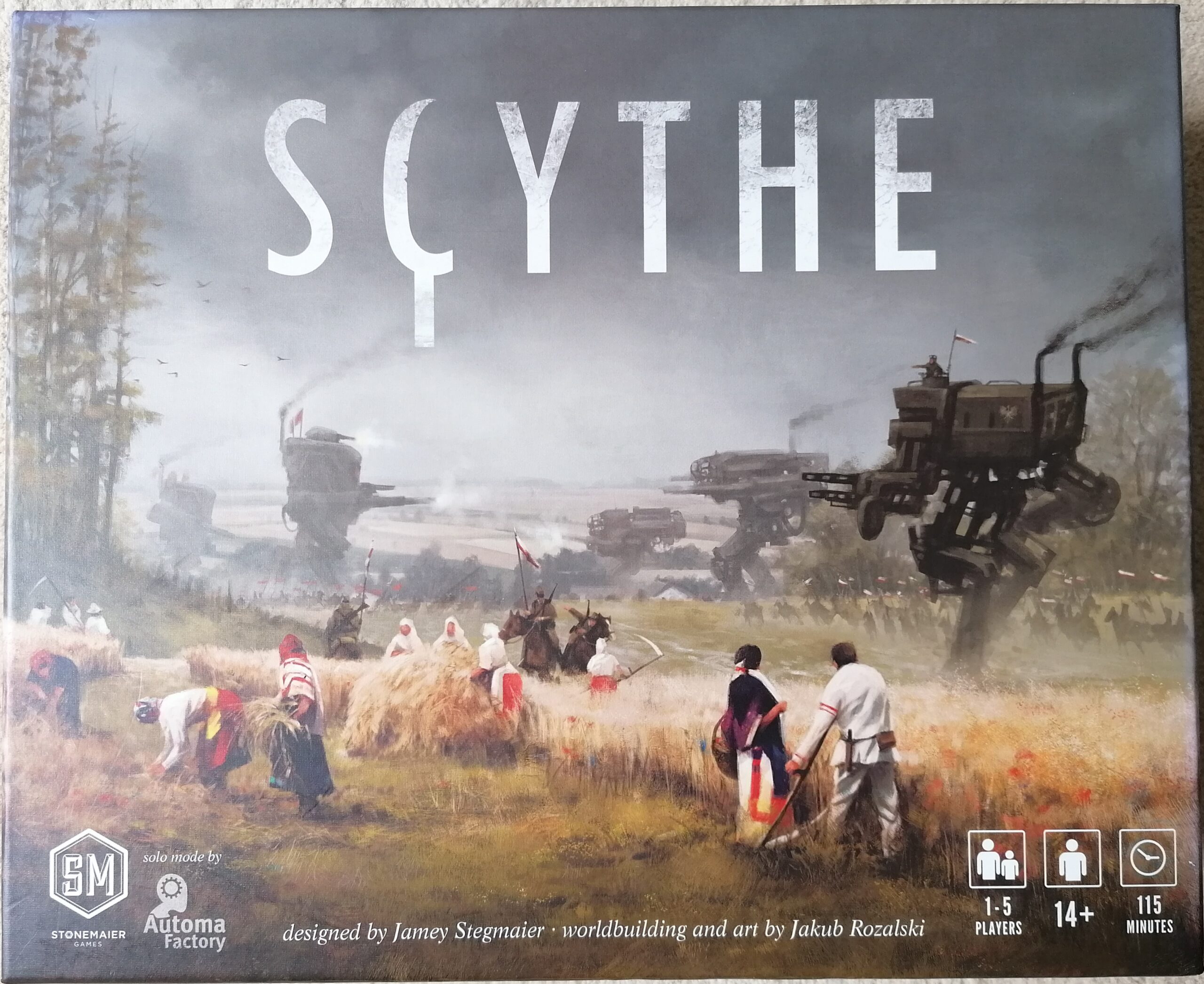

Since its release in 2016, Scythe has been a considerable hit within the board gaming hobby. Only fairly recently has it fallen outside of the top 10 ranked games on Board Game Geek, and at the time of writing, it still sits within the top 15. A game from Stonemaier Games and designed by Jamey Stegmaier, the game actually began with the art, or rather, the world. Set in an alternative history, called the 1920+ universe, created by Jakub Rozalski, Scythe takes place after the first great war, where five (in the base game) factions vie for control of land, build structures and deploy armies of mechs, amongst other things. On the surface, you may think that this is a war game, and therein lies an issue (of sorts).

Some people came to this game and expected it to be a big sprawling war game, with epic battles taking place between giant mechs. As the designer puts it, it’s a game more about the threat of war, but for those people who did have these expectations, it was a disappointment. A lot of people however, including myself, came into this either knowing that it wasn’t a war game (this is the camp I was in), or else having few to no expectations of what kind of game it was going to be. For me at least, knowing what this game was intrigued me, and I have come to really enjoy it.

The aim of Scythe is to amass the most coins at the end of the game, and you can do this in many different ways, most of which link to the ‘popularity track’ down the left-hand side of the board, which acts as a multiplier for end-game scoring. During the game you will be attempting to gain stars through various means, controlling hexes and gaining resources. Depending on where you are on this track, each star will be worth three, four or five coins, each hex will be worth two, three or four, and every two resources will be worth one, two or three. You can also just gain coins throughout the game, which will add to your score after you’ve applied these multipliers, and this will give you your total. Being the most valuable, stars can’t be ignored, but you can certainly win without obtaining the most.

There are nine different ways to gain stars in Scythe, which are all listed in the top left of the board, and you can place a maximum of six. Once someone places their sixth, the game ends immediately. This means that you can approach these in very different ways from your opponents, and this variety appeals to me greatly. I may want to try to obtain two of my stars from combat, which is the maximum you can gain with all but one faction, but then the next game I may want to try to avoid it, instead concentrating on other options, such as building my four available structures and fully upgrading my actions on my player mat. I love the flexibility here, as you can play how you want.

Your faction will help steer you down one path. Along with giving you asymmetric amounts of some of your resources, you will gain a special ability. As mentioned above, one will allow you to gain more than two stars from combat, but then one will allow you to spend one card, normally used for combat, instead of a resource, and as resources are worth coins at the end of the game, this could be a very handy ability. One other asymmetric part of your faction is your mech abilities. At the start of Scythe you will place all four of your mechs on your faction mat, one covering each ability. If/when you choose to deploy these on to the main board, you uncover the ability, meaning that going forward, all of your mechs, as well as your own individual ‘character’ piece, will be able to use it. Two are the same no matter which faction you play, but two will be unique to you. Again, like with the stars, it is completely up to you which ability you uncover and in which order, if you place any at all.

The action board however is where you’ll mainly be focused (or at least, as much as the main board), and it is here where Scythe truly shines. Along with giving you your remaining starting resources, and telling you who the starting player is, each board will be different in two ways. The actions at the top of the board will always cost the same, if there is a cost, but will be in a different order. The actions at the bottom actions will be in the same order, but the cost and additional benefit associated to them will differ. Each turn you will be placing your pawn on one of the four sections, and performing the top action, the bottom action, or both. Top actions will usually give you something, such as some resources, or allowing you to move up a track. Bottom actions will allow you to do more impactful things, such as deploying mechs or building structures, but cost a lot more to do. For me, working out how to make these top and bottom row actions synergise is a fascinating and satisfying puzzle. One game, the top row action to produce resources may be paired with deploying a mech and gaining two coins, which costs three metal (at least to begin with), but in another game this bottom row action may now have an initial cost of four metal, gain you no coins, and be paired with the top row action of moving your pieces on the board.

The majority of actions you choose to take in this game will impact the main board. It’s made up of various hexes, and at the top of each it will show you what type of hex this is, which directly relates to what you produce. The other type of player piece you can place on the board, alongside your character and mechs, are workers. These are the only pieces which can produce resources, deploy mechs and build structures, but they are the only ones that can’t fight (though they do force anyone who attacks them successfully to lose a popularity) and that can’t move across water without being carried by a mech. You start the game with two, and you can gain more by using one to produce on a ‘village’ hex, indicated by a meeple symbol. It’s another important aspect of the game you need to consider; do you want to put out as many workers as you can, increasing the cost every time you produce new resources, or do you want only a few, or even just your starting two, meaning you produce far less, but never have to pay to do so?

The main board of Scythe is huge, and is full of wonderful art which really captures the world, as well as containing fun little easter eggs (a popular Christmas character with a red suit and a white beard as an example). Yet the designer wanted to go beyond that, and make players feel a little more involved with the world, and so he added ‘encounters’ around the board, indicated by a compass-like symbol. When your character ends a move on one of these spaces (as long as it hasn’t already been taken by either you or another player), you gain a card, giving you three options, of which you can choose one (unless you have a certain faction), as well as an image related to the choices you have. The three choices will often follow the same pattern; gain a small reward for no cost, gain a slightly better reward for a small cost, or gain an even better reward for a larger cost. Personally, though I don’t necessarily feel a great thematic connection, I enjoy the addition of these, as it just gives you more options to explore.

I mentioned that Scythe is not a war game, but combat still does come into play, and how it is done is very interesting. Along the bottom of the board is the ‘power track’, and throughout the game you will have opportunities to move up this track, as well as collecting combat cards which can help you. When you do enter combat with a character and/or mech, each player involved will receive a dial, numbered zero to seven, which you will spin so that the amount of power you want to spend (as long as you have it to spend) is at the top. Then, depending on how many units you have in the combat, you can spend the equivalent amount of combat cards to increase that number, and then you both reveal. The loser’s unit(s) will be forced to retreat to their home base, as well as losing any resources that had been on that hex with them, and even though both the winner and loser will spend the power they committed, as well as any cards they added, the loser will gain a combat card. It could be worthwhile to purposefully lose a combat just to gain another card, and then attack your weakened opponent right back. The combat is just so easy in this game, and takes only a few moments to resolve. Again, people expecting, or hoping for, a big sprawling death match won’t find that, and may well be left wanting, but for me, it’s so smooth and quick that I can’t help but love it.

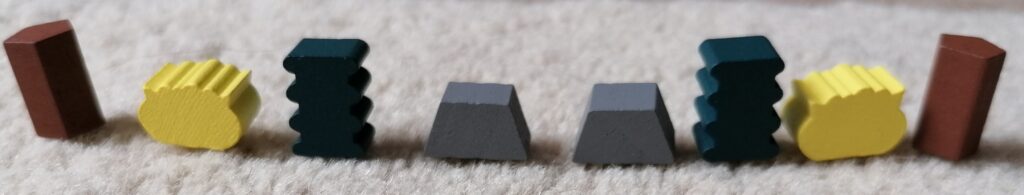

I have never played a poorly produced, or even averagely produced game from Stonemaier Games, and Scythe is certainly one of, if not the best, produced one yet. Each action mat is dual layered, meaning that each cube, worker and structure slots into it’s own spot. The structures are well made, large enough to stand out but small enough so that they don’t get in the way. As with all of their games, I appreciate that the resources are not just tokens, but individually shaped pieces. But the miniatures are the standouts. Now, I never played miniatures games, and I haven’t even played that many games with miniatures, but to me these are stunning. The character and differently designed mechs really elevate the experience for me, bringing a wonderful amount of tactility and grandeur to the game.

There is a lot to Scythe. It’s quite a rules heavy game, in relation to other games I have played from this company, and this may get in the way of some people’s enjoyment. At first, it did so for me. That, alongside the fact that, at least to begin with, it’s a slow game. It’s an engine-building game, and for the first few turns at least you can’t really see how you’re going to be able to build an efficient one. But once you understand it, the game flows excellently, and you can see how you’ll do it. For some, this will take one, maybe two games. For me, and probably many others, it took longer, but I wanted to keep going because I could see the potential, and I’m so glad I did.