Favourites from my collection

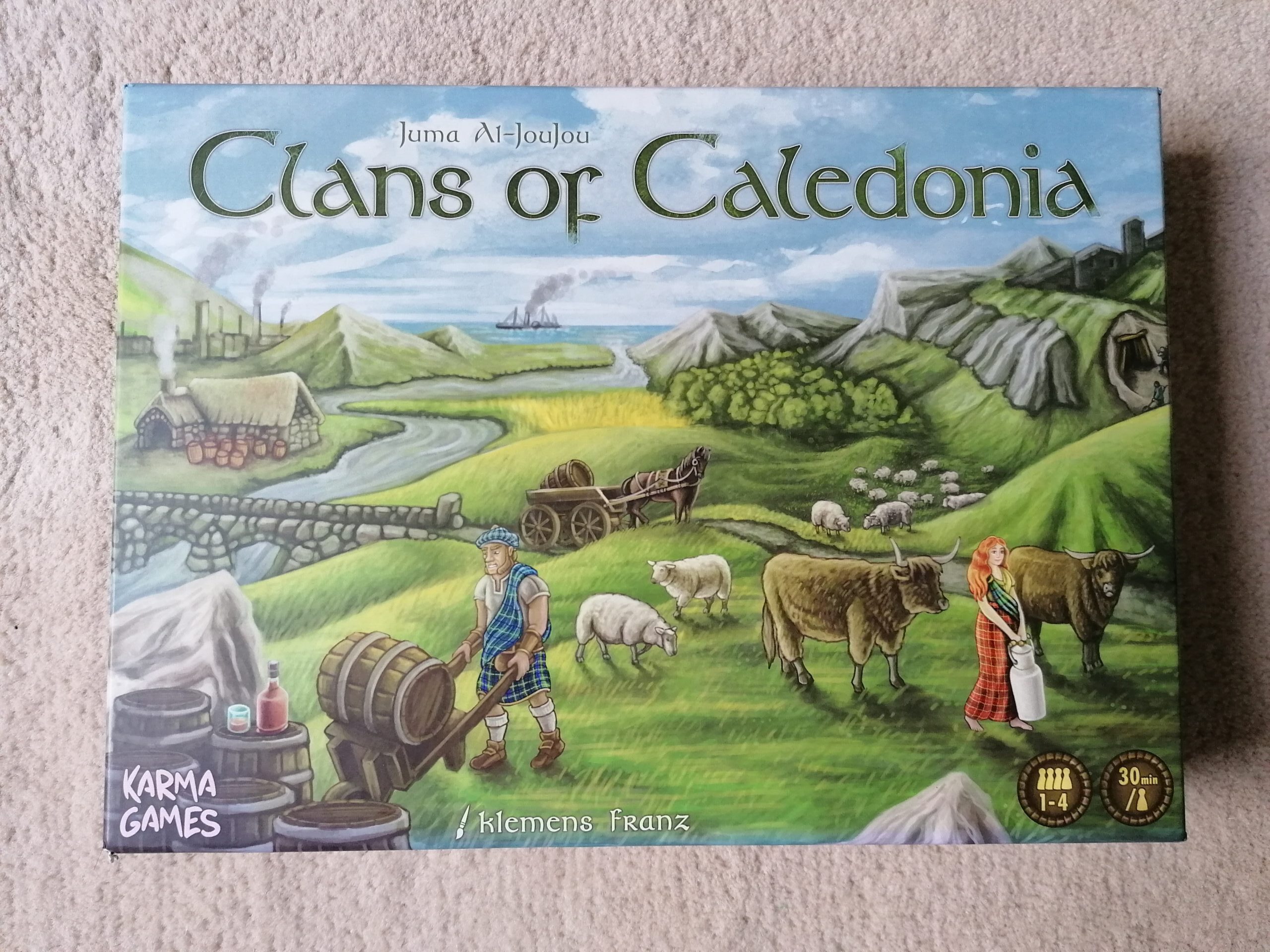

#1 Clans of Caledonia

From my first play of Clans of Caledonia, I felt like this game would be amongst my favourites, and over the years it has gradually moved up my list, and I have no doubts in my choice in it being my number one. If I hadn’t already made it clear in previous reviews, engine-building is my favourite mechanism, and the main reason for this is that, from the beginning to the end of a game, I feel like I have accomplished so much, and I’ve been able to personalise my experience, meaning I’m heavily invested in what I’ve been doing. For me, Clans of Caledonia gives me exactly what I’m looking for.

In this game, you’ll play as a Scottish clan, attempting to gain the most points through expanding your territory, producing and trading goods, and fulfilling contracts. At the beginning of the game you will choose which clan you will represent, and your starting resources. The clans add a lovely amount of asymmetry to the game, giving you rule-bending abilities. It may not sound fair, but as each player has one, the game is nicely balanced. To add a nice bit of theme to the game, the in-game clans are based on real-life clans from Scottish history, which is written about in the rulebook. Using an example from the photo, Clan Cunningham lived on incredibly fertile land, and used that to raise cattle, and therefore sold a lot of milk and butter. In Clans of Caledonia, their ability is that at the end of each round, you can sell any milk in your resource pool for a set amount of money.

Probably the most important thing in this game is money. You’ll always start the game with at least £55, and at first that may seem like quite a lot for a game such as this one. You’ll quickly realise it’s not, as you have to pay for almost everything in this game, and before you know it it’s gone. There are many actions you can take in Clans of Caledonia, but the main thing you’ll be doing is placing pieces out on to the board. Each type of piece you’re playing, whether cattle, a miner, a bakery or multiple other options, will have its own individual cost, but you also have to pay for the land on which you’re placing it. This is a simple addition to the game, but adds so much in the way of decisions. In game, you always have to place a new piece adjacent to something of yours already on the board, meaning that there could be up to twelve (or with one clan up to eighteen) potential areas in which to place. That, along with the fact that you’ll be trying to think two or three moves ahead, makes for a puzzle that entrances me.

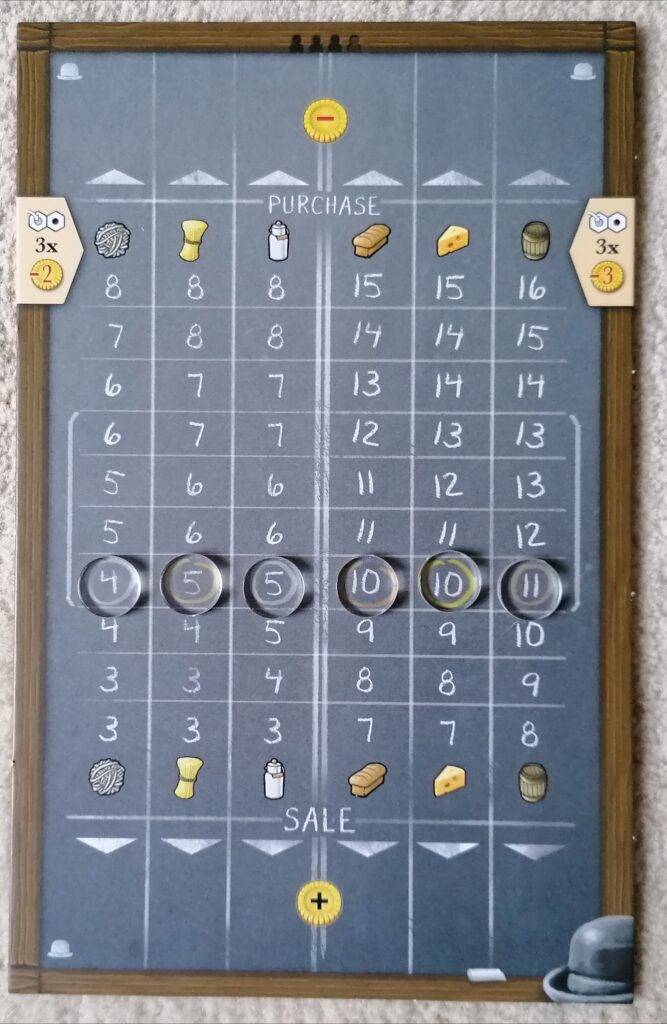

A way to make back some of the money you’ve been spending (other than just passing for the round) is by utilising the market, and again, this is a simple yet brilliant addition to the game. Most clans begin the game with two merchants, of which you can acquire more throughout the game. Each time you choose to take this action, you can commit as many or as few merchants to a single spot on the market, and can either sell or buy that much of a specific type of good (as long as you can afford them/have them to sell). You’ll buy or sell at the price indicated by the tokens on each track, but this isn’t the most interesting part. That comes with how players manipulate the market. For each unit of good that you buy/sell, after the transaction is completed, you’ll adjust the price by as many spaces as goods involved. As an example, if I sell three units of bread when the price is on £10, I’ll get £30, but then the token will move down three times, lowering the price. The opposite is true if you buy. Not only is this a nice thematic touch, as it’s representing how in demand goods are or aren’t, it also adds another layer of interaction to the game. In raising the price, you might make something unaffordable for the next player, or in lowering the price, you might be reducing the amount of money an opponent was planning on getting when they sold the goods.

Another part of the market that I enjoy links in with the board placement. Placing one of your pieces wouldn’t normally get you anything immediately, only in between rounds, but if you choose to place next to an opponent’s piece, you can unlock an adjacency bonus. Say you choose to place next to another player’s distillery. If you have unused merchants, you can now buy up to three units of whisky at a discount of £3 per unit. For any of the three ‘basic’ goods (wool, wheat and milk) this discount is only £2, but it can still be a useful bonus, and trying to plan around this could just save you enough money to allow you to perform one more action before you’re out of money. It’s a risky tactic though, because if you see that you’re only one step away from getting this bonus, then your opponent can probably also see it, so you might want to act quickly before your opponent capitalises on this situation.

Contracts are a part of this game that you can’t dismiss. Not only do they give you points (both in-game and end of game), many of them will also give you bonuses, whether it’s giving you some extra money, or allowing you to place a piece on to the board without having to pay for the land. All but one clan can only hold one at a time, which does allow you to focus, but because of this limitation, it may be in your best interest to complete them as quickly as possible so that you can move on to the next one. This is especially true early in the game, as in the first round you’ll receive £5 each time you use the action to take one (or up to two if you have the clan which can hold two), but by the final round of the game, you need to pay £15 each time you use this action, adding yet another excruciatingly intriguing decision to the puzzle. Fulfilling a contract is a separate action, where you just exchange the required goods and gain the benefits. Simple enough, but some contracts require meat, and this is a good that you can’t buy at the market or produce in between rounds. The only way to fulfil these types of contracts is to remove one or more of your cattle or sheep from the board, potentially temporarily harming the engine you have built up, but it may well be worth it.

Perhaps the smartest aspect to this game, and it’s another wonderfully simple inclusion, is how the contracts will get you end-game points. Most contracts will have a symbol in the top right-hand corner which relate to the three pieces shown in the picture on the scoreboard. These represent cotton, tobacco and sugar cane, and each time any player completes a contract with one of these symbols, that piece will move up the scoreboard the relevant number of spaces. At the end of the game, the piece which is furthest along the scoreboard is considered to be the most common ‘imported’ good, and is therefore worth the fewest number of points, whereas the piece furthest back is the rarest, and therefore worth the most points. Each player will count how many times these three goods show up on their completed contracts and multiply them by three, four or five points. I find this part so intriguing, adding yet more interaction in a subtle but brilliant way. I may choose a contract with sugar cane on it because I can see that it is currently the rarest good, but then an opponent may do the same. If we both complete those contracts, the piece may shoot in to first on the scoreboard, suddenly making it the most common, so it’s all a delicate balancing act.

I have played some engine-building games where you need to take five or six actions to get anything out of it. In Clans of Caledonia, every placement will eventually give you something, making you better and better with every move. Each piece that you take off your player board will reveal something underneath, showing you what each one will give you. If you place a field out, you’re going to be producing two units of grain. Here is also where the user-friendly nature of the player boards shines. There are arrows next to each basic good that can be turned into another good (a ‘processed’ good), showing you what else you need to have placed on the main board in order to do that. Using the same example, each unit of grain can be converted into bread or whisky, but only if you have a bakery or distillery out on the board as well. Another example is with the workers. Each worker will produce money, and that will accumulate based on how many you have out on the board. Rather than making you calculate how much money you will get though, it tells you on the board, adding it up for you with every worker revealed. Small touches like this really do make a difference, making it as easy as possible for the player, and not getting in its own way or putting a stop to the game while you work out what you’ll be getting.

A game that looks good in my collection is more likely to be played than others. There are some exceptions of course, but a lot of the time it is true. It adds to the experience for me, and Clans of Caledonia is, for me, one of my better-looking games. As I’ve mentioned, I love everything about the gameplay. Nothing feels clunky to me. It all just flows incredibly smoothly. Add to that the level of production in this game, and you have a game that I can never imagine saying no to playing. Instead of tiles to represent good, they have 3d pieces that are both lovely to look at and hold. They could have just had differently shaped generic pieces to represent different buildings, but they made them look like identical to the good (except in the player colours), making it easy to instantly tell what they represented. As above, the player boards are beautiful and easy to use. Even the contract tiles are smooth cardboard, giving them a wonderful tactility.

Clans of Caledonia isn’t going to be for everyone. As I’ve said before, no game is. The theme, while there, is not necessarily represented in the strongest way, and isn’t going to attract some people. For some it could be a little complex in terms of the depth of decisions, or even for some it could seem too simple in terms of the actions you take. None of this applies to me. Though others in my collection could switch places in my favourites, I can’t see this one moving anytime soon.